Architectural Essay - Year One: Deciphering Gothic Ideals

- Immanuel Ko

- Aug 10, 2017

- 10 min read

Essay Title: Deciphering Gothic Ideals

*My first essay of architecture school*

Gothic architecture is human ambiguity made stone. An ambiguity on portraying the themes of divinity, majesty, and unintelligible design.

Medieval Europe was undeniably shifted by the destabilization of the expanse which was the Roman Empire, however, this was far from a shift back towards barbarisms, but, instead towards artistic, philosophical, and political developments significant to the development of European culture. The era was heavily shaped by the underlying themes of religious and political expansions – in both Europe of Christendom, and further afield east towards the Mediterranean. Such expansions were significant to the formation of today’s Western States; Britain, France and Spain. With new empires naturally came titles that were adorned to heads of states.

Unprecedentedly, 12th century Europe saw the endemic intertwining between state and religion. Preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, the Catholic Church acted as the counter-part of the twinned socio-political power structure of Medieval Europe. The Church by the High Medieval period was expected to be at the forefront of every persons social and spiritual agenda, from; peasantry to the newly established medieval nobility, not even monarchs being exempt. Theology of the era had received a boon from the spreading affluence of the church throughout Europe; notable theologians of the time include; Robert Grosseteste Bishop of Lincoln (1175-1253) and his study ‘On Light’, as well as that of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274).

As a cumulative impact of these developments, spanning from the 12th century through to the 16th century, the most significant architectural feats of the High/Late-Medieval, or rather Gothic era took form in the shape of religious buildings.

Gloucester Cathedral

A critical representation of the English Gothic church. Rebuilt between the years 1089-1499, it embodies elements of not only the three chapters of the English Gothic evolution, but also Norman Architecture – an English variant of the Romanesque style (Gloucester Cathedral: 2017). Gloucester Cathedral holds a great deal of importance from both a historic and contemporary viewpoint. As a result of the 400 year construction period, today the Cathedral is finally completed and as such, Gloucester characterizes the distinctive, and at times subtle, transitions of the English Gothic style. It shows the transitions from the Romanesque style to the Early English Gothic, as well as the subsequent transitions to the Decorated and then Perpendicular styles of English Gothic architecture. Gloucester through a sense of assorted design history becomes somewhat of a physical encyclopedia for the English Gothic evolution.

The Early English Gothic was made up of; the lancet window, quadripartite ribbed vaults, slender spire towers and simply molded capitals with tall bases. The Decorated of; more geometric and elaborate window traceries, larger windows and increasingly diminishing wall spaces. And the Perpendicular; fan styled vaulting, panel style tracery windows, and elongated piers with clustered shafts, which would go to reinforce support to the vaulting (Yarwood 1985: 194-194).

Above: Quadripartite ribbed vaulting

It must be imagined at the time that the cathedral would have been a place on monastic study and a destination for religious pilgrimage, for those from afar, and with county. For those of the peasantry class a cathedral holds significance in both being a cultural center, as well as being a visual representation of taxes turned to stone and ornament (Jacobs 1984:17). Although taxes were never popular, and most likely never will be, there wouldn’t have been a great sense of resentment at the time. As most would have never have been able to experience and spend time in a place so architectural complex as this, a feat by any standard.

Above: Geometric window tracery.

Below: Panel window tracery.

[endif]--The question of purpose arises when looking at the countless renovations of Gloucester Cathedral. Why not simply keep to the original style of cathedral rather than encompassing all 3 stylistic periods of the English Gothic? Gloucester Cathedral holds a sense of competition within itself, each renovation attempting to be grander and sophisticated. Not just simply attempting to be more structurally advanced than each of its previous constructors, each patron commissioning architects to adapt to the cathedral was unafraid of the avant-garde.

It stems not only from the duration of the build, but more importantly the wider cultural influences, not just in England but also overseas in Europe, particularly France. As the early English patrons would have most likely have seen the sheer number of Gothic cathedrals and abbeys being erected in areas such as Ile de France, then reflecting back home on what boundaries existed and could be pushed in terms of design. This theory seemingly holds true when looking at perhaps very early Gothic buildings in England and then looking at the turn of the era towards the Renaissance, where we have the peak of Perpendicular in buildings such as the King’s College Chapel in Cambridge. The evolving nature wasn’t one that looked at disregarding the elements of the Gothic style, but one of improving them, elaborating them, sustain the feeling of disbelief in all that made pilgrimage to see them.

Above: Interconnected vaulting of the Decorated era of works

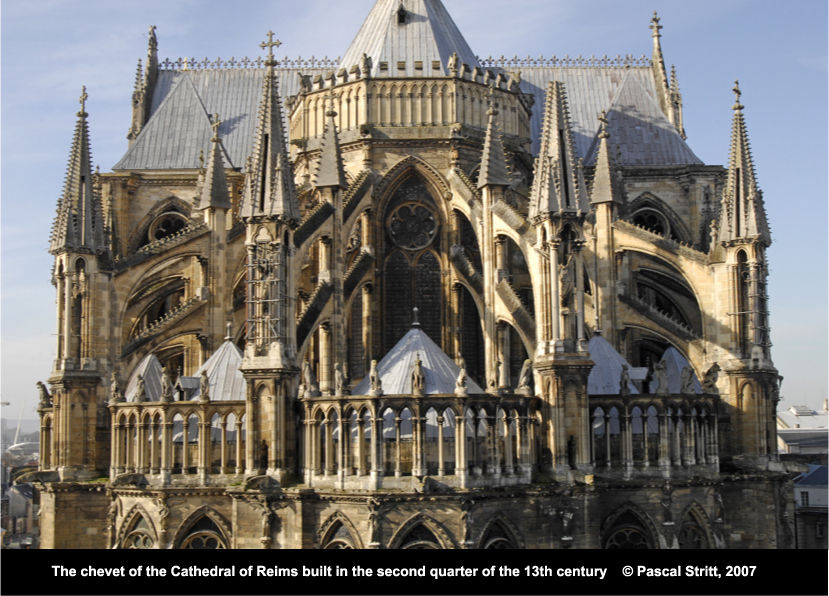

Cathedral of Notre-Dame (of Reims) 1211-1275

King’s in medieval Europe were not simply rulers of their respective lands, but reminiscent of Egyptian Pharaohs, was the belief that a King was the appointment by a higher power, by God. Even today in an increasingly secular state, Queen Elizabeth II is to some considered a representative of God, being crowned in none other than Westminster Abbey. So with the knowledge that the medieval era was a time of an even closer relationship between religion and society, we must acknowledge the medieval importance of the church’s relationship and heads of state.

A palace of kings is perhaps the most apt description of the Cathedral Notre-Dame in Reims, and the cathedral itself being the most appropriate Gothic build to look at for the idea of majesty. Historically before its erection in 1211, King Louis I ascended to the throne in Reims at the site which would later become Notre-Dame. Following which almost all French coronations took place at the cathedral (DRAC 2017). It seems an air of legitimacy was given at a time where existed many and changing monarchs throughout Europe.

The importance of legitimacy is exemplified in none other than King Henry of England. Henry VI. Although not as unforgettable as Tudor Henry, Henry VI’s coronation is of importance. Already crowned in England Henry VI was both ‘rightful’ King of both England and France, however, Henry VI was crowned at Notre-Dame de Paris and not in Reims. In short as a result of King Charles VII’s own coronation at Reims, a year before King Henry’s, Henry VI’s legitimacy was challenged (History Today 1982). This all going to show the importance of the cathedral in political terms.

In more social terms, the cathedral would’ve been central to a great deal of celebrations and pomp, there being nowhere as aesthetically appropriate to become a king in France. These celebrations would have been taken into consideration during the construction of the cathedral.

Above: Renovated gargoyle drain spout.

[endif]--As Ile de France, the region the city of Reims hailed, perceived itself to be the best of catholic France (Watkin 2015:150-156), the spirit of competition was very much alive. It’s this notion, much similar to English attitudes as seen by Gloucester, which would have encouraged patrons of Reims Cathedral to hold ambitions of none less than the grandest of designs; patrons would’ve been eager to enlist only the finest of craftsmen. The idea of majesty and ascension is clearly seen by the west front in which people would enter the cathedral by. Splendor is seen in the western portal’s pointed arches, as sculptures were carefully crafted to seem almost embedded into the increasingly withdrawing gables and glazed tympana.

Above: Gables of Reims Cathedral

Reims holds a mass of beautiful and realistic sculpture, also characterized by smiles and frowns. A development in realism and expressionism which isn’t found in very early medieval art is found at Reims: a style which has become identifiable with the Gothic style. The sculptures exhibited inside and out, provided an understandable theology for everyone, telling tales of stories such as the birth of Christ: essential in a time where neither did many have access to the means of religious texts, or the ability to even read them. Also adorned to the building were representations of kings, which begin to act as ascending upward division on the outer facade.

Some of the less ‘angelic’ figures located around the rest of the cathedral are displays of gargoyles. The demonic characters add an air of spiritual pressure, solemnness and fear to those before it, creating a sense of reflection in spirituality alongside the angels to those who came to visit. Beyond ornamentation however, gargoyles were too an example of civil engineering for the cathedral, as they would funnel the water out of their mouths and away from the building (French Moments 2012).

Ornamentation again assisted engineering as the use of heavy ornamentation on pillars on top of flying buttresses for added support by weight (Fitchen 1981:127). Lastly in engineering terms: the idea of ascension again comes from the wide and clear views found between the flying buttresses. The pointed arches made this possible; they push weight down, reducing the need for buttressing alongside the arch, traditionally previously done by thick Romanesque walls which act as a form of buttressing. By removed Romanesque ideas of solidity, giving Reims the impression of delicately resting between sweeping winds alongside its triumphant spires.

Basilica of St. Denis 1135

[endif]--It is perhaps most appropriate that the building considered to be the forefather of the Gothic style, is one that strongly exemplifies the style's most important architectural feature. Light. The ideas behind the light of St. Denis and subsequently the evolving Gothic style came from its patron, Abbot Suger. Or perhaps more accurately the influence medieval theologians had on Suger. Names such as Aquinas and Grosseteste, although both only coming to public light well after the Basilica’s completion in 1144, do reflect the trend of theological ideas of the medieval era. ‘God confers beauty on all things in that he is the cause of consonance and clarity in everything,’ (Eco 1988:64-66) and ‘God created first form, or light,’ (Stanford 2007) are translations of Aquinas and Grosseteste respectively. Where this draws relevance is that these words are from interpreters of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the same early medieval theologian Suger had too drawn inspiration from (Watkin 2015:150-156). On which Dionysius writes on all things being representative of the beauty (light) of God(Khan Academy 2012). Suger in response to the theological views of his predecessors and contemporaries, as well as the responses of all other patrons of Gothic churches, was an attempt at rationalizing and materializing their views on divinity.

Above: Altar of St. Denis

It is evident from this that light was at the nethermost ambitions of the Gothic style. Progression from the Romanesque to Gothic was not alone due to wishes for taller and daintier buildings. Although the English Gothic was an attempt at the ascent towards the heavens through stone, it was not conclusive for the style as a whole, as proven by St. Denis – as well as other French originating styles such as the High Gothic (e.g. Reims), and the Rayonnant, which St. Denis acted as the test subject for (Khan Academy 2012). Rayonnant synonymous for it larger windows and the rose shaped window face (Jacobs 1984:64-70), as well as its delicate bar tracery evident in St Denis’ chapel windows. St Denis’ achieves its ambition of light in its drastic renovations by the use of its ambulatory, interlocking vaulting and pointed arching.

Pilgrims at the time would travel to sites over many weeks in search of penance, healing and receiving the spirit of God through religious relics (Jacobs 1984:23-24). The previously walled off chapels were, in St. Denis, opened in form of the ambulatory (Khan Academy 2012),allowing people to walk past the chapel and pray in front of relics whilst basking in the light from the multi-coloured windows: prayer in the presence of divine light.

Right: Plan of St. Denis

As a result of creating an ambulatory, as well as the hollowing out of the church interior (by the combined efforts of the vaulting and the pointed arches), St. Denis achieves its patron’s ambition of flooding the interior with light. The experience of such in a church would have been something almost completely foreign to visitors at the time of its original completion. Entering through the west door attendees would look down the nave; seeing the vertical rhythms of slender columns that seem to draw upwards from the ground to the height of the church via its vaulting, earth rising towards heaven, a gaze meeting a ‘divine’ radiance from the chapels coloured stained glass and the adjacent ambulatory running below it.

Above: Procession to the alter of St. Denis

Succeeding Gothic Ideals

Seemingly impossible feats of height and stability were achieved with stone and glass through the use of the engineering principles; interconnected vaulting, pointed arching, and load distribution via the flying buttressing. A total beauty is created by the encompassing stained glass, ascending slender piers and ornamentation, crafted by glass workers, masons and sculptors. Gothic architecture was truly an attempt to rationalize and construct physical homes for the fluid, and changing medieval ideas on God. However this practice of attempting to materialize forms of subjective and immaterial concepts, this expressionism, did not simply end at the medieval period, in fact it is embodied by other religious buildings proceeding this.

Upon visiting Barcelona, Spain and seeing first hand Antoni Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia (starting construction in 1882), it is evident that the Gothic spirit remains. At the front of its Nativity façade one faces its soaring spires, its iconographic stories of the birth of Christ, beautifully hand carved into its gable, as well as its windows, partly reminiscent of Gothic geometric tracery. And upon entering through the facade, into the transept, and then approaching the nave, utter luminescence.

Above: Ceiling of La Sagrada Familia.

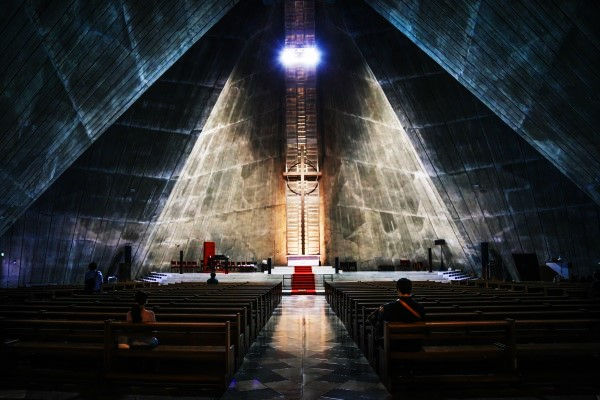

And yet still the Gothic influence has not been relinquished, as in Tokyo, Japan exists St. Mary Cathedral, a modernist take on immaterial expressionism. St Mary’s despite a rather polished 20th century material approach still embodies the Gothic elements. Its front elevation whilst resembling a metal crane like bird with its wings spread, still holds ideas of upwards ascension, as the glass façade encased between two metal vertical lines express an unending elevation. Other elements it retains is a cruciform shape, expressed by the wings of the cathedral. The ultimate reference to the Gothic by the cathedral is in a contemporary approach to light. Following the influences of; architectural writings such as Adolf Loos’ ‘Crime and Ornament’, the birth of minimalism, and purely the public cost of erecting buildings: in most cases it is no longer justified to make use of intricate tracery or stained glass. What St. Mary’s does however, is it carefully crafts tension between the dark shadows of the concrete interior, and the bisecting light splitting down the cathedral’s nave, almost alluding to the moral and spiritual struggle between good and evil, and reproducing ideas such as divinity by light.

Above: Altar of St. Mary’s.

Both buildings are exemplar in showing how Gothic forms and light have been modernized: expressing divinity, majesty and unintelligible design; how immaterial concepts such as faith and religion can and are still expressed through material, whether it be stone or metal.

Referencing

DRAC Champagne-Ardenne (2017) available from <http://www.reims-cathedral.culture.fr/origin-history.html> [11 January 2017]

Eco, U. The Aesthetics Of Thomas Aquinas. 1st ed.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988. Print.

Fitchen, J. The Construction Of Gothic Cathedrals. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981. Print.

French Moments 2012 available from https://frenchmoments.eu/reims-cathedral/ [11 January 2017]

Gloucester Cathedral (2017) architecture available from<http://www.gloucestercathedral.org.uk/history-heritage/architecture/ > [11 January 2017]

History Today 1982 available from http://www.historytoday.com/ct-allmand/coronations-henry-vi [11 January 2017]

Jacobs, J. The Horizon Book Of Great Cathedrals. 1st ed. New York: American Heritage Pub. Co. Bonanza Books, 1984. Print.

Khan Academy (2012) Birth of the Gothic, Abbot Suger and the ambulatory in the Basilica of St. Denis, 1140-44 available from <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2EciWH-1ya4> [11 January 2017]

Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy 2007 available from <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grosseteste/#ExeTruIll> [11 January 2017]

Watkin, D. A History of Western Architecture. 6th ed. London: Laurence King, 2015. Print.

Yarwood, D. (1985) Encyclopaedia of Architecture. London: B. T. Batsford

![endif]--![endif]--![endif]--![endif]--

Comentarios